Creating a Basic Synth in XNA 4.0 - Part I

This time I’ll be talking about how to create a very simple synthesizer in XNA (a little bit simpler than the one in the picture).

I’m by no means an expert in this field, but it is one that has interested me a lot lately. Unfortunately it is also a topic that I can’t seem to find much information online that is aimed at beginners. By writing this article I’m hoping to bring together a few bits of useful information for people who are just starting out, while at the same time forcing myself to learn more about it. With that disclaimer out of the way, if you find any problem with the article, then by all means leave a comment and I’ll correct it immediately.

Structure of the Article

The article will be divided in three parts:

- Part I will introduce the reader to the world of sound synthesis with XNA 4.0 and cover some of the basic theory that should be understood before proceeding.

- Part II will introduce the DynamicSoundEffectInstance class present in the XNA 4.0 framework and how it can be used to play some simple waveforms. By the end of part II you should be able to create and reproduce a single waveform of different kinds (such as a sine wave, sawtooth wave, pulse wave and square wave).

- Part III will guide the reader through the construction of a Synth class that allows the application to communicate with the low-level audio playback engine through a much simpler, music-oriented interface. The class will also be flexible enough for new sounds to be created and swapped easily. By the end of part II you should be able to play many musical notes simultaneously, while controlling their individual pitch, duration, volume and panning. You should also be able to create entirely new sounds and use them with minimal changes to the code.

The system presented here is currently intended for real-time use where notes are triggered in response to game events (e.g. a virtual piano keyboard). While there is always some latency between triggering the event and hearing the sound, by tweaking some of the values, it is possible to get it down to near real-time values, at least for the Windows platform (I haven’t tried it on the XBOX and WP7 yet).

Later I might write another series of articles building upon this architecture adding support for sequencing (programming a sequence of notes with their positions in a timeline and have the engine play them at a certain tempo) and plug-in effects (such as adding a flanger or delay effect on top an existing sound).

Preliminary Theory

XNA 4.0 opened new doors for audio programming by finally allowing the game to interact with the low-level audio playback engine directly. If you’re already familiar with XNA, then this low-level interaction is somewhat analogous to the SetData method of the Texture2D class, but for sounds instead. When using Texture2D’s SetData you usually provide an array of Color values, and each value will correspond to one pixel in the final image.

With sound you’ll also be providing an array of values, but unlike Texture2D, the relation between these values and the resulting sound is not so obvious. Nonetheless, since you can submit any values you want, it is possible to implement virtually any sound or sound application imaginable, which makes it very powerful in the right hands. Before jumping into any implementation details, let’s start by understanding the relation between these values and the sounds they create.

What exactly is a sound? Sound occurs due to vibrating objects creating pressure oscillations in the atmosphere which are then captured by the eardrums and interpreted by the brain as the sounds that you hear. Different oscillations will result in different sounds. For instance, a strong oscillation will generate a loud sound while a weak oscillation will generate a soft sound and a fast oscillation will generate an high sound while a slow oscillation will generate a low sound. Many other factors also come into play and turn each sound you hear unique, letting you distinguish the sound of a piano from that of the human voice.

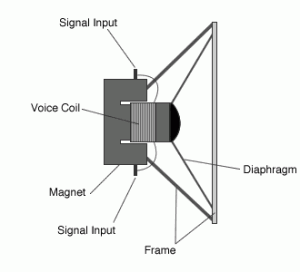

It is also interesting to know in very general terms how most loudspeakers work in order to understand how sound can also be artificially generated. Take a look at the diagram below.

Loudspeaker Diagram

Loudspeaker Diagram

The diagram represents a loudpseaker seen from the side, but the circular piece in the middle is known as the diaphragm (or cone). If you look into a set of loudspeakers as they’re playing, it’s the piece that will be moving around. When an electrical current is fed to the loudpseaker, its mechanism causes the diaphragm to move back and forth on its axis. This in turn modifies the air pressure around it and generates the sort of oscillations that our ears can capture. It makes sense then to think that with the right algorithm to move the diaphragm, it is possible to generate pretty much any sound that we desire. But first we need a way to represent our data.

Waves, Waves and More Waves!

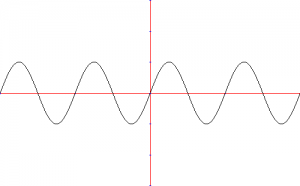

As described earlier, the oscillations that generate sound are essentially variations of air pressure over time. In mathematical terms, any sort of disturbance over time is called a wave, and has a very straightforward way of being represented in the form of a graphic of how its amplitude varies with time. The graphic below represents a simple sine (or sinusoidal) wave:

Regular Sinewave

Regular Sinewave

A single sine wave such as this is also referred to as a pure tone because it has only one frequency. On the other hand, most sounds that you hear are extremely complex sounds that result from the sum of many simple pure tones at different frequencies and phases in relation to each other (see additive synthesis).

I’m assuming that you already have a basic knowledge of wave theory, but if you’re completely new to this then for the scope of this article it should suffice to know that the wave’s amplitude is basically how strong it is (measured in the y-axis), and the wave’s frequency describes how fast or how often the wave repeats itself (measured in the x-axis). For a concise explanation check this link.

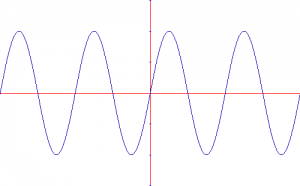

Both the amplitude and the frequency affect the sound significantly, but in very different ways. For instance, the wave represented below has the same frequency as the one above, but has a larger amplitude. This means that as a sound, it would sound louder than the previous one:

Louder

Louder

On the other hand, the wave below has the same amplitude as the first one, but has a larger frequency. This results in a sound with the same volume but an higher pitch:

Higher Pitch

Higher Pitch

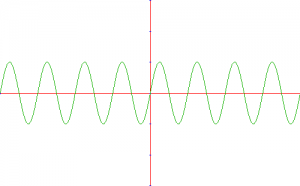

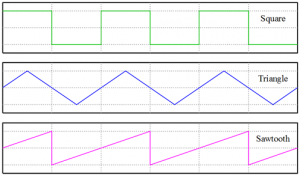

Last but not least, we have to recall that most sound waves do not have a perfect sinusoidal shape. In fact, sound waves can have virtually any shape, and each of them will result in an entirely different sound. The figure below shows some common types of waves in sound synthesis (which we will be implementing in part II).

Other Shapes

Other Shapes

Wave Implementation

So now we know that any sound can be represented mathematically in the form of a wave. Then how can we represent a wave in code? The answer is quite simple: as a function that takes the time as a parameter and returns the amplitude of the wave for that particular time.

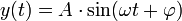

If you’re trying to represent a wave that you’ve never done before, then the first step should be to look up a mathematical formula for it. For instance, the wikipedia article on sine waves shows the following formula:

Where:

- A = Amplitude

- ω = Angular Frequency (in radians per second)

- φ = Phase

For the sake of simplicity, if we assume the amplitude to be 1, the phase to be 0 and the angular frequency such that the wave repeats itself exactly every second (i.e. 2π radians per second), then we could represent such a wave as follows:

double SineWave(double time)

{

return Math.Sin(2 * Math.PI * time);

}

Sampling Rate

By this point we already know what sound is, how it can be represented mathematically, and how it can be represented in code. However there’s still one important detail that hasn’t been discussed.

At the very beginning I mentioned that we’ll be providing an array of values for XNA’s audio engine to process. But as everyone knows, an array has a finite amount of elements. On the other hand, a wave is a continuous function, which means it has an infinite amount of values. Therefore, in order to convert from the continuous domain of the wave to the set of discrete values that our audio engine can handle, we need to compromise somehow. The solution is to consider only a few of the values of our wave function each second (where for our goals of creating music, a few will usually be an amount larger than 22.000 Hz).

How many samples to take per second (also known as the sampling rate) is a decision that will have a large impact on the quality and fidelity of the generated audio. If the sampling rate is too low, then some details of the original signal may be lost when converting to discrete values. According to the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, in order to perfectly reconstruct a signal, the sampling rate needs to be at least twice the maximum frequency of the signal being sampled. Since the average human can’t hear anything above the 20.000 Hz frequency range (although some can), the sampling rate used by audio CDs (44.100 Hz) is usually more than enough for all general usages.

Sampling Rate

Sampling Rate

Conclusions

This concludes the first part of this series of articles. Next time we’ll be putting these concepts to use and making all of these types of waveforms ring using the XNA 4.0 Framework. Besides revisiting the sampling rate describe here, we’ll also see some other important aspects of audio playback such as bit depth, audio channels, latency and buffer size. See you again soon!